Material, memory, and the choreography of perception

Ryan Sun

In Barthroom Experimental Gallery in Jingdezhen, Silk in the Mist is such an exercise in perception and not a presentation of discrete works. The exhibition places material as importance not as a vessel but an act agent entangled with atmosphere, memory, and the body.

Sakaizon’s inflatable rubber installation responds to real-time barometric changes, liberating form from stasis and pulling the body into relation with the environment. The material swells and contracts like a lung, transforming architecture into a breathing organism.

Sakaizon’s work is not an object but a condition. It stages a negotiation between the body and atmosphere, collapsing distinctions between sculpture and environment. What emerges is a kind of architecture of sensation, where space itself becomes porous, alive, and unstable.

Sophy Qi’s two-part installation stages a dialogue between selfhood and the cosmos, where personal experience is refracted through allegory and myth. Two large-scale photographs anchor the work: one a self-portrait taken during the artist’s time in Korea, the other a vast image of the waves at Busan. Together they hold a tension—one gazes inward, intimate and fragile, while the other disperses outward, toward infinity—locating the personal within the immeasurable scales of nature and history.

Before the images, an assemblage unfolds: a Republican-era iron chair supports a plastic water jug, within which rests a desiccated branch. These everyday objects—chair, vessel, water—are stripped of their function and rendered uncanny. What once promised rest or circulation now becomes an empty reliquary. The withered branch, poised between relic and specimen, acts as a mute allegory of vitality suspended, a condensation of growth, decay, and memory in a single form.

Qi’s work resists closure. It inhabits the space between mourning and renewal, intimacy and distance, the terrestrial and the celestial. Her installation does not declare meaning but rather suspends it—an atmospheric field in which the viewer is asked not to interpret, but to dwell.

Sun Sun’s installation unfolds as an uncanny choreography of containment and recurrence. A single droplet of water, filmed and looped, plays ceaselessly on a smartphone screen. The device—suspended within a hermetically sealed casing shaped like the inside of a functioning toilet—becomes both stage and cell, a microcosm where time is arrested yet endlessly cyclical.

The looped drop resists narrative progression—its incessant repetition evokes both stasis and insistence. In this context, the droplet is not merely water but time made visible: each cycle becomes a soliloquy of duration. By enclosing this minute act within an object designed for evacuation and flow, Sun Sun inverts expectation. Where a toilet is typically a conduit for elimination, here it becomes a vessel for preservation.

Rooted in Jingdezhen’s porcelain traditions, Lu Jianxing repositions ceramic practice within a contemporary sculptural frame. His work bridges centuries of craft with experiments in form and placement.

Lu treats tradition not as a relic but as a living reservoir. His ceramics destabilize the idea of heritage as static, insisting instead on continuity through transformation. The result is sculpture that resonates with both historical weight and present vitality.

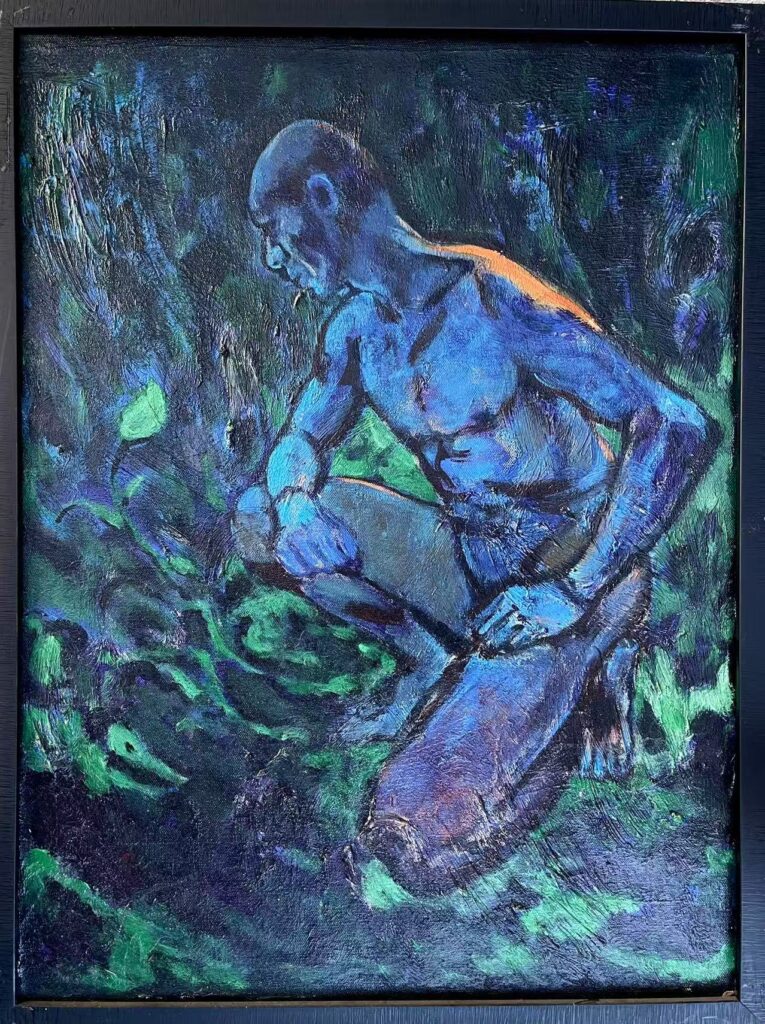

Tang Qiang’s paintings reframe classical oil language through gestures of embodiment and land. His canvases become territories, mapping affect and physicality rather than cartography.

Tang’s landscapes are not vistas but bodies—paint is walked, smeared, and stretched like earth underfoot. He transforms painting into a choreography of place, binding memory and geography through the sensuous materiality of oil.

Huang’s paintings are rooted in mysticism, folklore, and cosmological systems—from the Five Elements to astrological charts. Her canvases pulse with rhythm, balance, and elemental transformation.

Huang offers a poetics of the cosmos: symbols and colors act less as representations than as incantations. Her works are visual chants, time-keeping devices that invite meditative viewing. They ask the viewer not just to see but to tune into the rhythm of the universe.

After leaving the gallery, one does not encounter a catalog of objects but a recalibration of perception itself. “To squint” becomes, both metaphor and method, a way of living in uncertainty, of letting the form dissolve into sensation. Silk in the Mist does not become financially closed. It is an exhibition unraveling thread by thread to suggest that meaning is not given but relentlessly woven in the blurry.